An Introduction to Sanskrit: The Language of Yoga

Jan 04, 2019

संस्कृत

saṃskṛta

“refined, ornamented, perfected”

देववाणी

devavāṇī

“language of the gods”

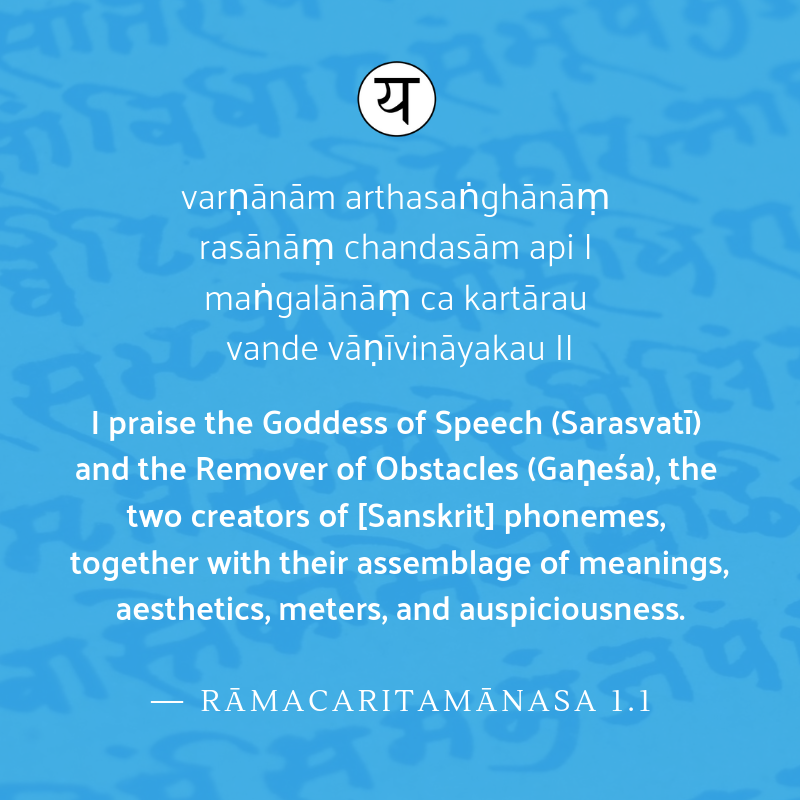

Sanskrit is one of the most ancient continuously used languages in the world. Known by tradition as the language spoken by the gods (devavāṇī), it is understood as the “perfected” language (saṃskṛta). For many, Sanskrit is revered as the language and voice (vāc) of the entire cosmos—the vibratory ground of reality itself (śabda-brahman). In the Ṛg Veda, Vāc is personified as a Goddess, from whom the entire world assumes its multitude of forms. In later Hindu traditions, this Vāgdevī is understood as Sarasvatī, the Goddess of the arts, music, wisdom, and learning.

“Thousand-syllabled [voice] in the sublimest heaven…

descend in streams the oceans of water;

It is from her whence

the four cardinal directions derive their being;

It is from her whence

flower the immortal waters;

It is from her whence the universe assumes life.”—Ṛg Veda 1.164.41-42 (trans. Mahoney 1998)

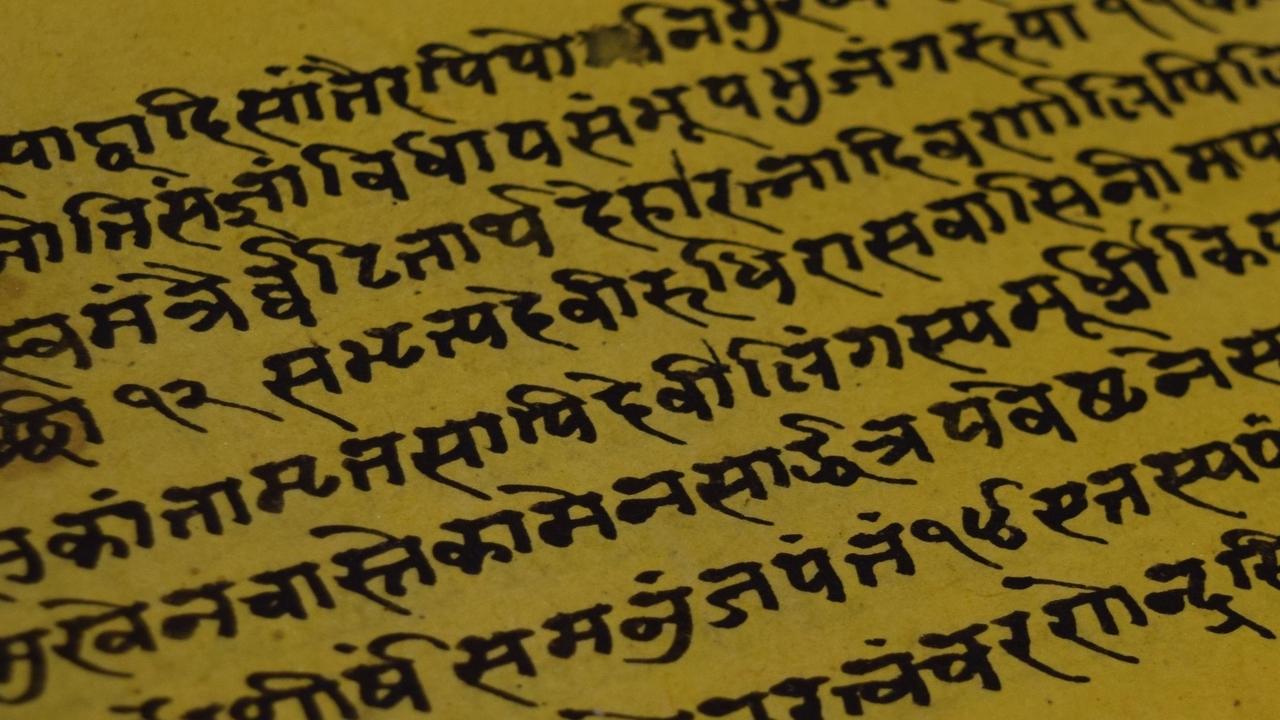

For thousands of years the sacred soundscapes of Sanskrit have profoundly shaped Indian religion, culture, and society. The early Vedic tradition (c. 1500 BCE) gave primacy to the power of the spoken language and the efficaciousness of its aural sound above and beyond the written word. The Vedas—the earliest expressions of the Sanskrit language—were understand to have been originally heard (śruti) by the Vedic seers (ṛṣi). These hymns were then passed down from mouth to ear, from father to son, through familial lineages of highly specialized Vedic priests. From a young age, these Brahmins encoded these Sanskrit scriptures onto their minds and bodies through an elaborate mnemonic system of language training involving recitation, bodily movements, hand gestures, and the synchronization of breath. Since this earliest period, Sanskrit mantras—efficacious sound techniques—such as the syllable OṂ (said to encompass all of the Vedas), have continued to be chanted, sung, offered in sacrifice, and meditated upon for spiritual benefit.

The system of classical Sanskrit was formally codified by the great Indian grammarian Pāṇini (c. 500 BCE) in his famous work the Aṣṭādhyāyī (Eight Chapters), comprised of approximately 4,000 terse aphorisms or sūtras. In classical and medieval India, Sanskrit served as the dominant intellectual, spiritual, and cosmopolitan language of the arts and sciences. Throughout the first millennium of the Common Era, Sanskrit literature and scriptures spread wide across the broader South and Southeast Asian world, forming what Sheldon Pollock has called the great “Sanskrit Cosmopolis.” Innumerable hymns, works of poetry, literature, dramas, religious, and philosophical treatises have been composed in this beautiful, complex, and ancient language.

Sanskrit is also the primary language of Yoga (yogabhāṣā). While today we are most familiar with texts such as the Yogasūtra, the Bhagavadgītā, and perhaps a selection of Haṭhayoga treatises, in premodern India, hundreds of yoga scriptures were written in Sanskrit, often on dried palm-leaf manuscripts—yet only a small percentage survive today.

As an Indo-European language, of the Indo-Iranian branch, Sanskrit is linguistically related to Greek, Latin, Persian, German, Russian, and the modern “romance” languages including French, Italian, and even English. Within this broad Indo-European family tree, we might say that Sanskrit is something like the great-great-great Aunt to English. For this reason there are many linguistic cognates between English and Sanskrit. Take for example the words manas and "mind", nāma and "name", madhya and "middle", and so on.

Given the striking affinity of the verbal roots and grammatical forms across these distant Indic and European languages, eighteenth-century philologists (those who study texts and language), such as Sir William Jones (1746-1794), a supreme court judge stationed in Calcutta, theorized (with the aid of his local Brahmin informants) the possibility that Sanskrit along with Latin, Greek, and Persian, likely all originated from a common source—a “Proto” Indo-European language that no longer exists.

Over time the transregional “perfected” (saṃskṛta) language gave way to the regional “natural” (prākṛta) ones, which later produced the common vernacular languages spoken in contemporary northern India and Nepal (e.g., Hindi, Marathi, Nepali, etc.). (The languages of southern India [e.g., Tamil, Kannada, Telugu, etc.] descend from a different language family, and are commonly referred to as Dravidian languages.)

While Sanskrit is commonly pronounced a “dead” language, comparable to the Latin of medieval Europe, the so-called death of Sanskrit is a bit misleading. Though Sanskrit has for the most part ceased to be a primary spoken language, or “mother tongue” (mātābhāṣā), in India, the language is still very much alive for the millions of Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain practitioners who continue to employ it in their daily religious and ritual life; for the paṇḍitas (scholars) of India and the West who continue to train in, compose, and read Sanskrit texts and manuscripts; and in some small way, Sanskrit is very much alive for the tens of millions of practitioners of yoga around the world—even if their pronunciation is not always “perfected” (saṃskṛta)!

May this little book be of service in keeping the great traditions of Sanskrit alive. May it offer insight into the depth and history of this language. May it offer a slight vocal “adjustment” in pronunciation for non-Indic speakers. And may it be a small lamp (pradīpikā) of knowledge (jñāna) on the path for all those who hold these traditions dear.

This post is an excerpt from the Introduction to Seth Powell's workbook, Yogabhāṣā: A Concise Introduction to the Sanskrit Language for Yoga Teachers and Practitioners. The text, along with an MP3 audio album are included with enrollment in the online course, SKT 101: Sanskrit for Yogis.